The goal of metastatic breast cancer treatment is to prolong survival with as few medication side effects as possible. Whether a person may wish to continue treatment is an individualized decision.

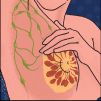

Metastatic breast cancer is the most advanced stage of breast cancer. It occurs when cancer cells spread beyond the breast tissue and nearby lymph nodes and begin affecting other organs, such as the liver, lungs, brain, and bones.

Various treatment options are available for metastatic breast cancer, including:

- chemotherapies

- hormone therapies

- immunotherapies

- radiation therapy

- surgery

- targeted medications

Advancements in breast cancer care have improved outcomes in recent years, but the outlook with metastatic breast cancer tends to remain unfavorable. Among people in the United States with metastatic breast cancer, less than

Many people with metastatic breast cancer may reach a difficult point in their care when the cancer is no longer treatable. This article includes experts weighing in on the factors people can consider when deciding whether to continue treatment or pursue other care options.

“Many factors go into the decision to stop cancer-directed treatment,” explained Cassidy B. Campanella, DNP, APRN, FNP-C, a nurse practitioner working in breast oncology at the Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah. “This decision is just as influenced by an individual’s values, goals, and definition of quality of life as it is by the extent of their cancer, medical complications, and functional status.”

People’s individual goals during treatment for metastatic breast cancer treatment may vary from person to person. They may also change over time. Typically, treatment goals involve:

- prolonging life

- reducing symptoms

- improving quality of life

“For many people, metastatic breast cancer treatment can be incredibly helpful, giving them years of additional time and help with symptoms,” said Kate Lally, MD, a palliative care specialist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. “Having said that, a time may come during treatment where a person’s goals are no longer being met. The treatment may no longer be prolonging their life, or life prolongation may not be a priority to them anymore.”

Treatment may also no longer be working for a person if the side effects of the medication outweigh the benefits they are receiving. “For example, treatment might be giving them additional time, but much of that time is spent in a hospital or with a heavy symptom burden that is difficult to live with,” explained Lally.

If a person is not happy with their current treatment plan, they may choose to pursue other options before stopping treatment altogether. “There are a lot of different options or ‘lines of therapy’ that might be available, and certain cancer centers also offer a variety of clinical trials,” noted Campanella.

“It is important that people have a good relationship with their oncologists and oncology team to think about the pros and cons of treatment at all stages,” said Lally. “Additionally, connection to a social worker or a palliative care team can help identify priorities at any given time and determine if ongoing treatment fits in with those priorities.”

“If someone is reaching a point where ongoing treatment is not consistent with what matters most to them and their goals, transitioning towards comfort-focused care where quality of life is prioritized can be important,” said Lally.

“Even when someone decides to stop cancer-directed treatment, this does not mean that we stop treating them from a symptom and quality of life standpoint,” said Campanella. “Attention shifts to what is most important to the individual and what they need to feel as good as possible for as long as possible.”

Medical care after stopping cancer treatment can involve the use of palliative care. These services focus on relieving symptoms and providing emotional, social, and spiritual support. As people approach the end-of-life phase, hospice care may also be part of the care plan at home or a hospice facility.

“[These care teams] can help provide intensive symptom-focused care to allow someone to feel as good as possible and support doing the things that are most important to them, such as spending time with friends or family,” explained Lally.

With palliative care, clinical visits may become less frequent, and people typically have fewer tests, procedures, and exams performed. Discontinuing all testing, procedures, and even follow-up visits for people getting hospice care is common.

“This is a welcomed relief for some and anxiety-producing for others, as we stop examining their body with a microscope and take a step back to look at the whole picture,” Campanella noted. “This often means more time at home with loved ones and healthcare that focuses on good symptom management in addition to supporting a person and their family as they navigate a new chapter of their life.”

“The decision to stop treatment is often made over time and in collaboration with someone’s healthcare team as well as their family,” explained Lally. She noted that these conversations should be based on a clear picture of what matters to the person receiving treatment and how they want to spend their time, no matter how much they have left.

“If ongoing treatment is helping to meet those goals without undue burden, then it likely makes sense to continue,” she said. “But if someone is starting to have significant symptoms as a result of treatment, it may make sense to consider stopping treatment, particularly if those symptoms are taking time away from loved ones.”

“My advice is to never be afraid to ask questions and always share what is important to you and what scares you,” said Campanella.

“Honest conversations about the ongoing burdens versus benefits of treatment are essential,” Lally agreed. “It can often be difficult for families to hear that a loved one wants to stop treatment, so speaking honestly about your concerns with ongoing treatment and the hardships that may result is important.”

For people who need support navigating these difficult conversations with their healthcare teams or family members, a palliative care specialist or hospice professional can help put their goals and concerns into words. Additional online resources are available through professional organizations and support groups.

The decision to stop treatment for metastatic breast cancer is a highly personal one based on a person’s response to treatment and their individual goals and priorities. When the benefits of cancer treatment no longer outweigh the burden it places on a person, they may choose to stop treatment and pursue other options to preserve their quality of life as long as possible.

Healthcare teams and loved ones can help support people with metastatic breast cancer as they consider their options. “Having the confidence and courage to have hard conversations well before any decisions have to be made can make handling the many unknowns of the future so much easier,” concluded Campanella. “It can also greatly reduce stress, both around ongoing hard conversations and around big decisions like stopping treatment.”